When setting out to build a new website or web application, it is a good idea to build a shared understanding of the product between stakeholders and the product team. Through research and collaborative activities that aim to answer questions about the product, its goals, and its users’ needs, the stakeholders and product team discover the full breadth and depth of the application to be built, as well as contexts and implications that need to be considered for the product to be successful. We call this process product discovery.

A study conducted by the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE) found that software development projects fail when they do not address stakeholders’ needs adequately. It has also been shown that 50% of programmers’ time is spent on avoidable rework. By devoting resources upfront to build a solid, shared understanding of project goals, users, and user contexts, you can ensure that you will be building the right solution and minimizing waste.

Product discovery can be approached as a four-step process:

- Frame the problem

- Identify the users

- Map out user actions, tasks, and workflows

- Sketch out ideas

Steps 1 and 2, framing the problem and identifying the users, get you started with understanding the ramifications of your product. Step 3, mapping out user tasks and workflows, is a way to define user contexts and begin exploring solutions. Finally step 4, sketching out ideas, is a step toward articulating a solution.

In this article, I will focus on steps 1 and 2. Steps 3 and 4 will be covered in the second installment of this two-part series.

Frame the problem

When framing the problem(s), you are striving to answer the following questions:

- What problem(s) am I trying to solve?

- For whom am I solving this problem?

- Why am I solving this problem?

- What does success mean and how can I measure it?

- What constraints do I need to accommodate?

Answers to these questions may be drawn from your business analytics and existing user or customer research. Data that inform your answers may come from:

- Competitive audit

- SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis

- User or customer interviews or surveys that reveal pain points, needs, and goals

- Existing use and engagement patterns

- Points of drop-off or failure, etc.

If data in those areas are lacking, you may start out by making assumptions and stating hypotheses that you will later put to test.

Identify the users

You can identify your users by asking questions such as:

- What are the demographic, psychological, and behavioral characteristics of the users?

- What are users’ goals, needs, and pain points?

- What user outcomes do I need to support?

- What are the workflows my users employ?

- How do users interface with my product?

- How do users leverage technology in their life and/or work?

- What types of solutions would best serve the users?

- Other questions about your users’ lives and work, and their interactions with products similar to yours.

You can gain answers to these questions by conducting user research including:

- Usability testing (observing people using an existing product or a competitor’s product)

- User interviews (talking to users directly about their workflows, goals, needs, and pain points)

- User surveys (having users answer questions, usually online)

- Contextual inquiry (observing users in the context in which they use or would use your product)

Armed with the data, you can then develop user profiles called personas. Personas are tools that allow you to consolidate information about your users into a succinct format, and, perhaps more importantly, give your users a human face. Personas are documented user profiles. But they are also a device that helps you identify with your users and develop empathy for them. It is particularly true in the case of so-called proto-personas — user profiles not based on actual data, but rather on assumptions and guesses you make about your users.

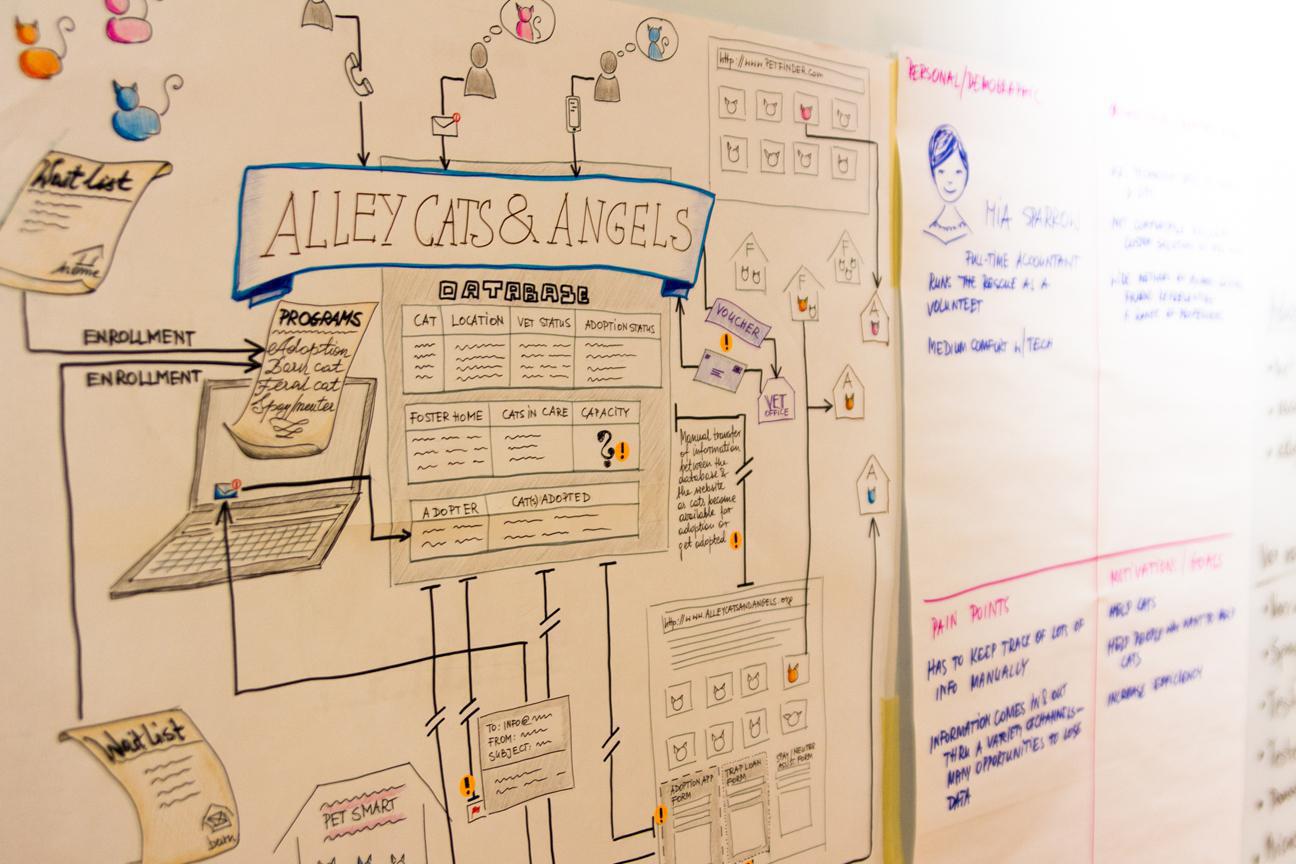

A sample proto-persona done at Caktus for an animal rescue

Personas (or proto-personas) include information grouped into categories, and there are multiple suggestions about good categories to use.

In Lean UX, Eric Ries recommends grouping information about users into:

- Sketch and name

- Behavioral and demographic information

- Pain points and needs

- Potential solutions

Ladies that UX suggest the following information categories to build a persona:

- Bio and demographics

- Emotions and behaviors

- Goals

- Solutions

In User Story Mapping, Jeff Patton shares a persona template that includes:

- User type and role

- Name and sketch

- Context

- About

- Implications

Next, strive for deeper understanding and explore solutions

Once you’ve gained an understanding of the problem you are solving and the characteristics of the users, you’re ready to dive deeper into user contexts and to start considering solutions. In Part 2: From User Contexts to Solutions, I will discuss techniques that can be leveraged to explore user contexts and ways to start identifying solutions.